A Clean Slate Design Using Netidx

In the last example we added netidx publishing of one data point, and then explored what we could do with the data. In this example we're going to look at a system designed from scratch to use netidx as it's primary means of communication and control.

The system we're going to look at is the control program of an off the grid solar generator. The system uses a Prostar MPPT controller, which has a serial port over which it talks modbus. Connected to this port is raspberry pi 3, called "solar", which is connected to wifi and joined to samba ADS.

The control program is a simple translation layer between the modbus interface of the Prostar and netidx. Full source code here.

The main loop takes commands from either the local command socket, or the netidx publisher, and sends them via modbus to the charge controller, e.g.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { loop { ... match msg { ToMainLoop::FromClient(msg, mut reply) => match msg { FromClient::SetCharging(b) => { send_reply(mb.write_coil(ps::Coil::ChargeDisconnect, !b).await, reply) .await } FromClient::SetLoad(b) => { send_reply(mb.write_coil(ps::Coil::LoadDisconnect, !b).await, reply) .await } FromClient::ResetController => { send_reply(mb.write_coil(ps::Coil::ResetControl, true).await, reply) .await } ... }

A message is either a timer Tick, on which we send out (and log) updated stats, or an actual command, which we handle individually. The publisher module is fed a new stats record read from modbus on each timer tick. e.g.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn update(&self, st: &Stats) { use chrono::prelude::*; self.timestamp .update_changed(Value::DateTime(DateTime::<Utc>::from(st.timestamp))); self.software_version.update_changed(Value::V32(st.software_version as u32)); self.battery_voltage_settings_multiplier .update(Value::V32(st.battery_voltage_settings_multiplier as u32)); self.supply_3v3.update_changed(Value::F32(st.supply_3v3.get::<volt>())); self.supply_12v.update_changed(Value::F32(st.supply_12v.get::<volt>())); self.supply_5v.update_changed(Value::F32(st.supply_5v.get::<volt>())); self.gate_drive_voltage .update_changed(Value::F32(st.gate_drive_voltage.get::<volt>())); self.battery_terminal_voltage .update_changed(Value::F32(st.battery_terminal_voltage.get::<volt>())); ... }

These are all published under /solar/stats, there are a lot of them,

so I won't show them all here, you can read the full source if you're

curious. Essentially it's an infinite loop of read stats from modbus,

update netidx, flush netidx, loop.

What About Control

The above handles distributing the stats perfectly well, but for control we need some way to send commands from the subscriber back to the publisher, and that's where writes come in. If you've read the api documentation you might have noticed,

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub fn write(&self, v: Value) }

Continuing with the metaphor of exporting variables to a cross machine global namespace, it fits perfectly well to imagine that we can write to those variables as well as read from them, publisher willing.

Our program is going to publish three values for control,

/solar/control/charging (to control whether we are charging the

batteries), /solar/control/load (to control whether the inverter is on

or off), and /solar/control/reset (to trigger a controller

reset). These values will all be boolean, and they will be valid for

both read and write. Here is the full code of the control section,

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { struct PublishedControl { charging: Val, load: Val, reset: Val, } impl PublishedControl { fn new(publisher: &Publisher, base: &Path) -> Result<Self> { Ok(PublishedControl { charging: publisher.publish(base.append("charging"), Value::Null)?, load: publisher.publish(base.append("load"), Value::Null)?, reset: publisher.publish(base.append("reset"), Value::Null)?, }) } fn update(&self, st: &Stats) { self.charging.update_changed(match st.charge_state { ChargeState::Disconnect | ChargeState::Fault => Value::False, ChargeState::UnknownState(_) | ChargeState::Absorption | ChargeState::BulkMPPT | ChargeState::Equalize | ChargeState::Fixed | ChargeState::Float | ChargeState::Night | ChargeState::NightCheck | ChargeState::Start | ChargeState::Slave => Value::True, }); self.load.update_changed(match st.load_state { LoadState::Disconnect | LoadState::Fault | LoadState::LVD => Value::False, LoadState::LVDWarning | LoadState::Normal | LoadState::NormalOff | LoadState::NotUsed | LoadState::Override | LoadState::Start | LoadState::Unknown(_) => Value::True, }); } fn register_writable(&self, channel: fmpsc::Sender<Pooled<Vec<WriteRequest>>>) { self.charging.writes(channel.clone()); self.load.writes(channel.clone()); self.reset.writes(channel.clone()); } fn process_writes(&self, mut batch: Pooled<Vec<WriteRequest>>) -> Vec<FromClient> { batch .drain(..) .filter_map(|r| { if r.id == self.charging.id() { Some(FromClient::SetCharging(bool!(r))) } else if r.id == self.load.id() { Some(FromClient::SetLoad(bool!(r))) } else if r.id == self.reset.id() { Some(FromClient::ResetController) } else { let m = format!("control id {:?} not recognized", r.id); warn!("{}", &m); if let Some(reply) = r.send_result { reply.send(Value::Error(Chars::from(m))); } None } }) .collect() } } }

In process_writes we translate each WriteRequest that is targeted at one of the published controls into a FromClient message that the main loop will act on. So from the main loop's perspective it doesn't matter if a command came from netidx or the local control socket.

Note that it isn't necessary to do any authorization here, the publisher library has already checked that the resolver server granted the user making these writes permission to do them, and of course we can control who is authorized to write in the resolver server permissions.

For the basic day to day use case, that's all we need on the server side. The entire daemon uses 6.5 MB of ram, and almost no cpu, it could certainly run on a smaller device, though we depend on tokio, which means we at least need a unix like OS under us.

The kerberos configuration for this service is also quite simple, there is a service principal called svc_solar in samba ADS, and solar has a keytab installed for it, as well as a cron job that renews it's TGT every couple of hours.

Building a Custom GUI With Views

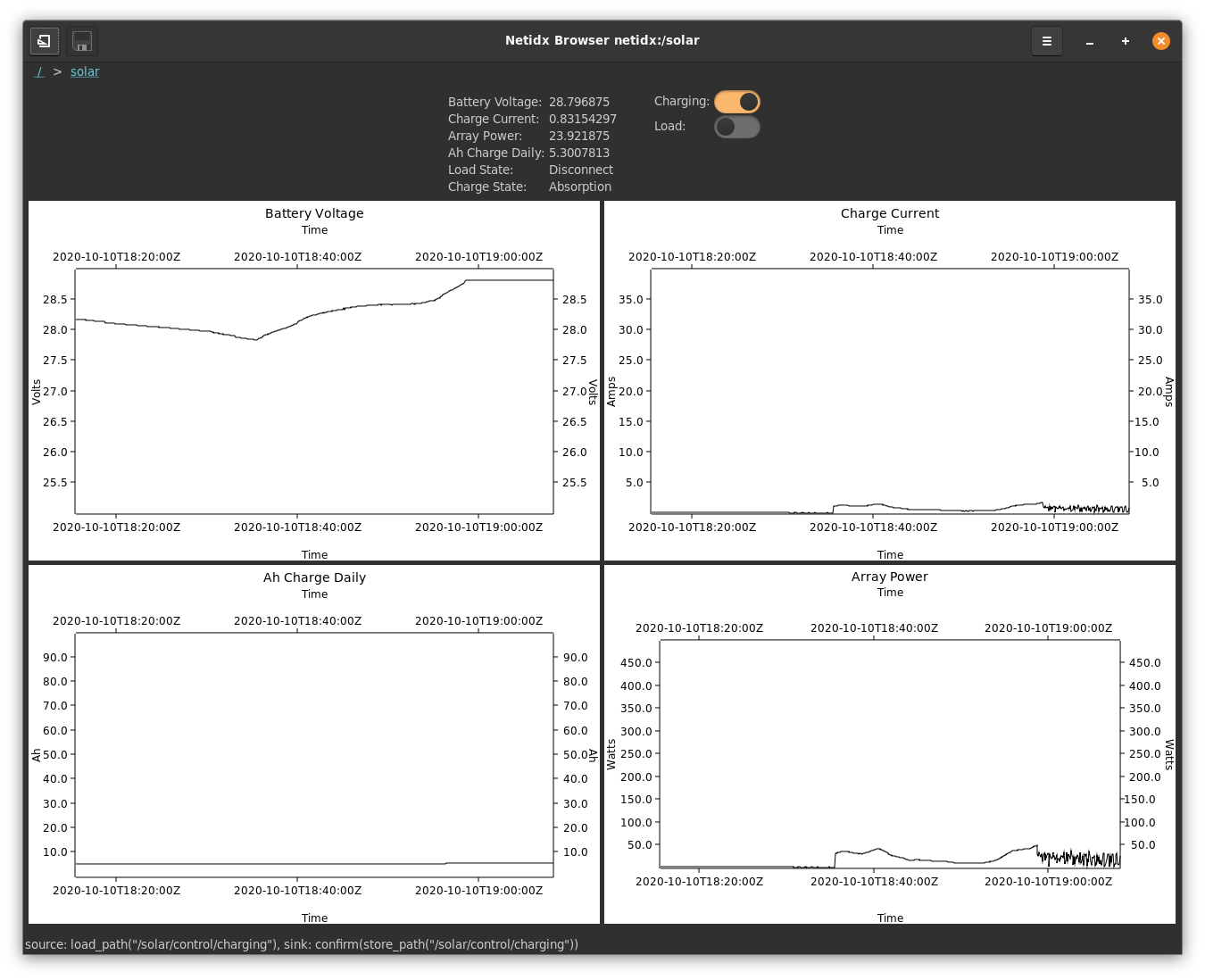

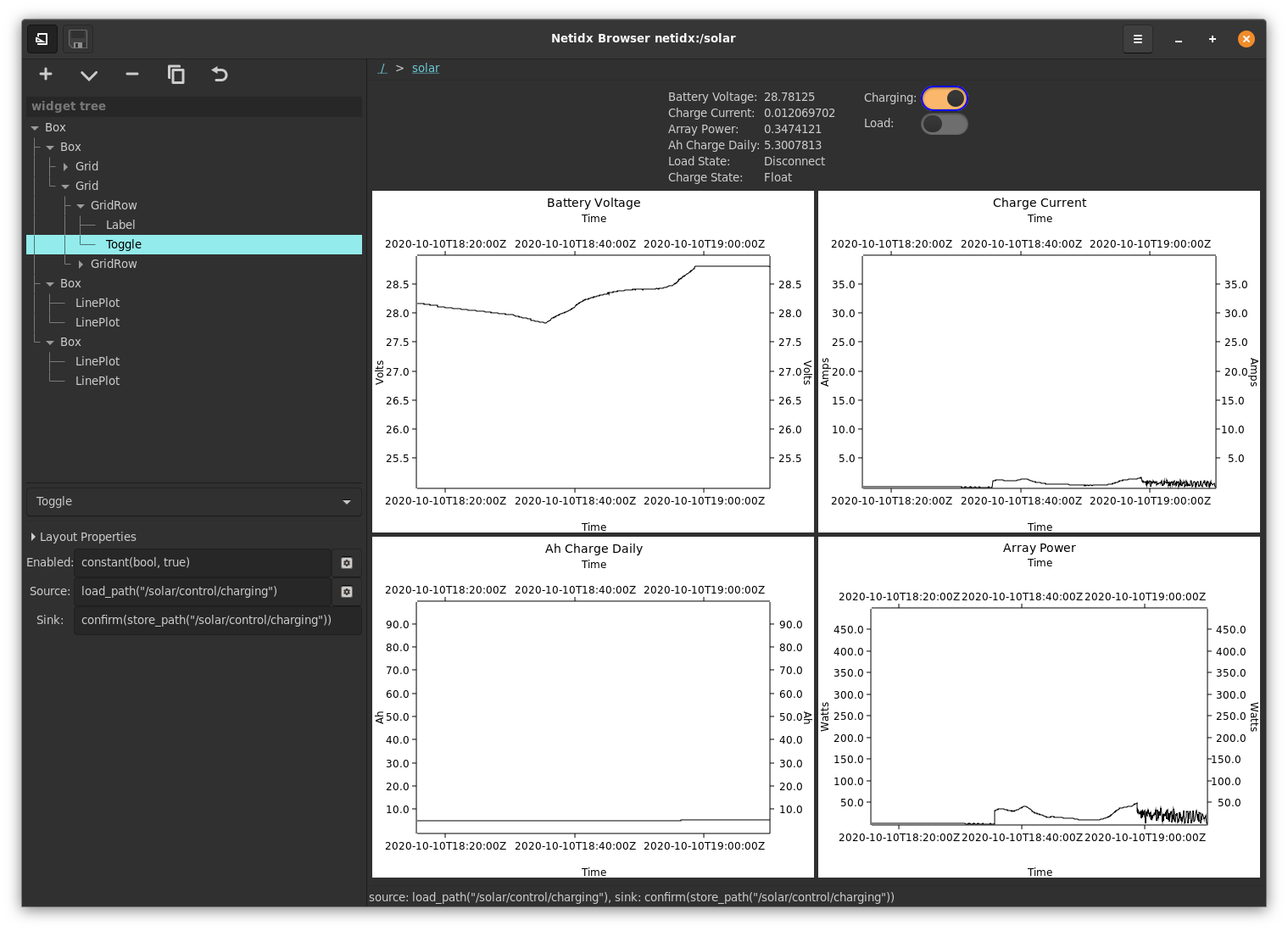

What we have is fine as far as it goes, we can view our stats in the browser, and we can write to the controls using the command line subscriber. It's fine for scripting, but I'd also like a gui. e.g.

This can be built using design mode in the browser, the view can then be saved to a file or written directly to a netidx path.

See the GUI Builder chapter for more information.

Wrapping Up

In this example we saw how an application can be designed more or less from the start to communicate with the outside world using netidx. We didn't cover the opportunities for scripting our solar installation now that we can control it using netidx, but we certainly could do any of the nice things we did in the last chapter. We did show an example gui, and I want to point out that having a gui in no way alters our ability to script and manipulate the system programatically. It's important to recognize that building a bespoke system with a gui as complex as the one we built AND making it scriptable over the network in a discoverable, secure, and performant way is not an easy task. Usually it just isn't worth doing, however by using netidx it was easy, and that's really the point of the whole thing.